A Sea Change in 2018 for Emergency Preparedness

“While each year the hurricane season comes to an end on November 30, the lessons from the response and recovery operations that we are performing this year, under incredibly difficult circumstances, will transform the field of emergency management forever.” - FEMA Administrator Brock Long, November 30, 2017.

Building a culture of emergency preparedness is now the national policy

On December 18, 2017, President Trump released his National Security Strategy which made building a culture of emergency preparedness the national policy. Two weeks before that, we heard FEMA Director Brock Long discuss the need to build a true culture of preparedness in the United States and that this needs to be a whole community effort. Mr. Long noted that we have to ensure that state and local governments have their own life sustainment capabilities and that FEMA was never meant to be the “first responder.”

What does this mean for emergency managers and citizens in our communities? First, we need to consider what happened in 2017, recognize a basic vulnerability in our default mindset and to consider the effect it has had over the years on our emergency preparedness. Finally, there is a solution. And the solution requires all of us.

The strength of our emergency management system is also a critical weakness

We operate under a basic principle: when an incident overwhelms the local capabilities, we can bring in outside resources from surrounding towns, the state and the federal government. This principle has served us well in disasters large and small. But have we grown dependent on this principle as the answer to every disaster? We depend on the availability of outside resources. Help is always a phone call away.

Until it is not.

In the fall of 2017, the U.S. was struck by 4 major disasters in rapid succession: Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Maria and the unprecedented California wildfires. (See Brock Long’s testimony to Congress here.) While each of these was a regional event – not a national disaster – taken together, they strained FEMA almost to the breaking point. FEMA was heroic, dedicated and I can’t identify anything worthy of criticism in their responses to these catastrophic events.

In the case of Maria, as Mr. Long points out, FEMA ended up as “the primary responder and pretty much the first responder, which is never a good situation. When FEMA is the first and primary responder, and the only responder for many weeks, we are never going to move as fast as anybody would like.”

One emergency management professional had this comment on one of my previous articles on this subject:

"In my many years of experience, we have created an environment of entitlement. The first question asked should be: 'what do I need to prepare or recover?' But unfortunately, it is often: 'what are you going to do to help me prepare or recover?' And one step further in some cases, the latter is in a form of a statement rather than a question."

But honestly, as bad as it was, the fall of 2017 was not a “worst-case scenario.” I say this because in each event – and in all 4 events collectively – outside resources were available to be deployed into the disaster area(s). Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and California made the call and the federal government answered and responded immediately.

What is a worst case scenario?

A worst-case scenario would be when our primary assumption fails us: there are no outside resources available for a long period of time. Nobody answers the phone call for help. The nightmare of any emergency manager or citizen: Your town is on its own and the cavalry is not coming.

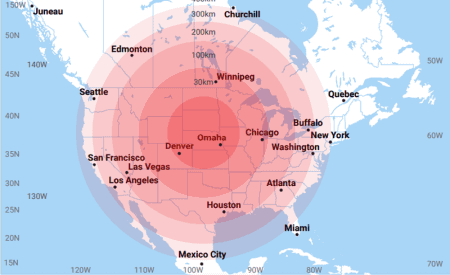

There are many plausible scenarios where this could happen, but the easiest to illustrate the point is an event that takes down a substantial portion of the electric grid. For example, a cyber-attack, an electromagnetic pulse (EMP), a geomagnetic disturbance (GMD or solar flare), a coordinated terrorist attack, extreme weather, etc.

There are many plausible scenarios where this could happen, but the easiest to illustrate the point is an event that takes down a substantial portion of the electric grid. For example, a cyber-attack, an electromagnetic pulse (EMP), a geomagnetic disturbance (GMD or solar flare), a coordinated terrorist attack, extreme weather, etc.

In this scenario, substantially the entire United States becomes the disaster area. And in each affected town and city the only resources available are what you have right now. Every town around you is in the same boat and the whole country is taking on water fast. But you don’t have time to think about that. Your local real-world problems are mounting:

- The power is completely out for the foreseeable future.

- Your local ham radio operator reports that the entire country is in turmoil.

- People are panicking – the stores and pharmacies have been looted.

- The police don’t have the resources to maintain order.

- Water and sewer service is out. Well pumps don’t work without electricity.

- People will soon run out of whatever food they have.

- There are reports of numerous fires – the fire department is overwhelmed.

- The medical facilities are overwhelmed, have no power and limited supplies.

- People are at risk of exposure to the elements and disease.

There is no help coming – your town is on its own.

The federal government is thinking about this. The National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2017 requires that the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security “include in national planning frameworks the threat of an EMP or GMD event.” FEMA recently released its “Power Outage Incident Annex: Managing the Cascading Impacts from a Long-Term Power Outage (POIA).” In fact, the federal government has been studying, debating and holding hearings for two decades on such threats. (See an extensive list of federal documents here.) Most of America has not been paying attention.

We ignore these threats – and the possibility of a national-scale catastrophe – at our peril.

Survival is a local issue - the cavalry is not coming

Even if you find it “unlikely” that a worst case scenario could happen, planning for it has great benefits to your community’s emergency preparedness. If we have planned for the worst case, we have thought about and planned for the problems we would face in our community in all hazards and in any disaster. We are more prepared and resilient as a community. Nothing wrong with that.

Over three months after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, there are still many people without power and access to clean water. So we can’t say that we can’t envision a scenario where things might be bad for a long time – weeks or months. And remember: this is “only” a regional disaster – Puerto Rico is not on its own. We have been able to devote massive national resources to the problem and it is still this bad!

We all need to ask ourselves: What would our community do if we were on our own for an extended period of time? What can we do now to give ourselves the resources and options that we’d need? (Does this sound suspiciously like “pre-disaster mitigation”?)

A thought that probably comes to mind: we don’t have the resources – nobody does. True, if we think inside the box. We usually think of resources as a budget line item.

But there is a way to create our own resources in our community. This is the key. We need a resource multiplier.

Brock Long told us how

His exact words: “The key resiliency is held at the local level of government…it’s going to have to be a whole community effort on the pre-disaster side.”

The community is your resource multiplier. Think of it. In your community you likely have people with every needed expertise:

- Doctors, nurses, EMTs and paramedics.

- HAM radio operators, communications experts and electrical engineers.

- Experts in various crafts such as construction, welding, plumbing and electrical.

- Former military and retired law enforcement personnel.

- Former Peace Corps volunteers who have worked in austere environments.

- Farmers and people who are experts in food production.

- People with homesteading knowledge who can teach others self-reliance skills.

- Health, safety and sanitation experts.

- Mechanics and engineers.

- Faith-based and non-profit groups experienced in disaster relief, outreach and fund raising.

- Business owners who know how to get projects from concept to production.

- Regular citizens who are willing to help in a variety of capacities.

- Etc., etc.

For virtually any problem that you can think of in a “worst-case scenario” you likely have somebody with the expertise to find solutions. Right now, these are your untapped resources. We just need to find ways to engage them.

It’s too late after the disaster happens (when we will all have an awful case of “gee, I wish we had…”). This is why meaningful pre-disaster mitigation is critical. Let’s identify the problems and solutions now – and, most importantly, work to have solutions and resources ready when a disaster happens.

Build a town civil defense organization

Civil defense is the organization and training of citizens to play a key role in the community’s emergency preparedness and survival after an attack or disaster. So, if we can somehow organize the above resources (people and expertise) and focus the organization on pre-disaster mitigation, imagine what we could do. And we have not touched the town emergency preparedness budget.

One way to do this is to set up a 501(c)(3) nonprofit civil defense organization in your community. (Some volunteer ambulances and fire departments are structured this way.) The organization can raise its own funds through donations. You can use an existing plan or create your own.

The important thing is to tap into this vast resource pool in your community and focus (i.e., lead) the community’s efforts in emergency preparedness.

You can’t do it alone or with your present budget. The good news is that you don’t have to. The cavalry is not coming. It is already in your community.